Experiential knowledge does not necessarily refer to the notion of knowledge, but rather to the fact of personally experiencing something and feeling it. Thus, experiential knowledge enables the individual to mobilise resources in the face of situations and feelings, in order to move forward and build up.

Experiences that are initially disconnected from each other are structured into « experiential knowledge », real know-how that can be capitalised on for others in the professional field. We can also call these competences, skills and know-how acquired (experiential knowledge) by the peer worker « cultural capital » according to the formula of the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu or a « know-how with domination » according to Demailly’s expression, close to Amartya Sen’s notion of « capability ».

According to Demailly, peer workers have the experience of domination, all have carried the stigma of domination.

Experiential knowledge has an emotional and empathic dimension, and this is a dimension that is difficult to capture. Moreover, it is difficult to objectify and measure quantitatively, as it is inherently individual, subjective, evolving and diverse according to Godrie.

Unlike experiential knowledge, academic knowledge is scientifically recognised, measurable and rationalisable.

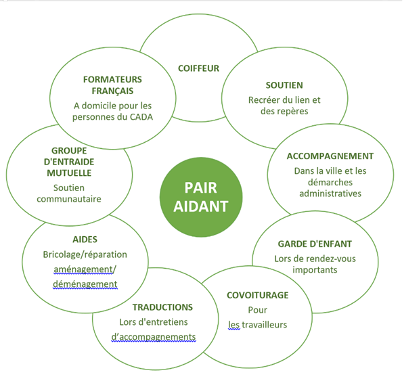

It is the mixing and use of this different knowledge and their mutual recognition that brings real added value to the field of social action and professional integration of migrants.

Indeed, « not all knowledge is lived », it is important that the peer helper who mobilises his or her experiential knowledge has specific skills, in particular, the ability to step back from his or her own experience (reflexivity), a sense of communication (active listening) and to avoid projecting onto his or her own experience. Experiential knowledge is individual and cannot be generalised.

A working group was set up following several referrals of refugees in an addiction situation to addiction health professionals in the area. These referrals very rarely resulted in regular follow-up. The CADA therefore set up a working group with addictology professionals and peer helpers who had experienced addiction problems (products and modes of consumption, weight of society and traditions, treatment methods) in order to determine the obstacles to supporting the migrant public in reducing risks. The results were as follows:

✅Lack of consideration for interculturality in support,

✅Language-related communication difficulties,

✅Lack of appropriate awareness and prevention tools.

These same peer helpers, with their wealth of experience, were able to provide a cross-section of views to the professionals but also to their peers by running workshops in the accommodation on addictions and the products used in the various countries.